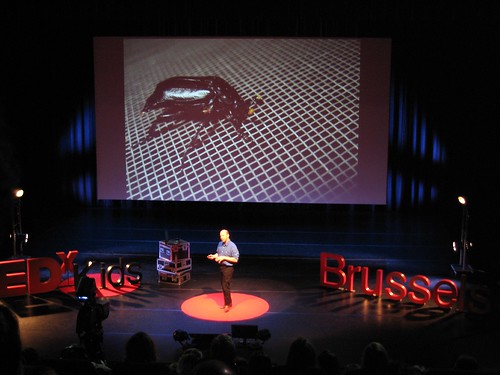

Last week (June 1st) the gang at TWSU (Technology Will Save Us) and I took two groups of about twenty 10-yr-olds through a basic soldering workshop as part of TEDxKids Brussels 2011. This was both one of the most tiring and most inspiring workshops I’ve ever taught, with the added bonus that directly afterwards we gave our TEDx talk!

We commandeered a team of 15 (if I remember correctly) dedicated, teenaged, volunteers to keep making at a maximum and burning at minimum. And when I say dedicated, I mean dedicated – I saw them soldering with the kids, sawing wood with the kids (in a later workshop), even taking a hit from a hot soldering iron to protect the kids. (I think they had some fun doing it, too). A big thank you to Daniel and Bethany for taking care of most of the organization, including making these cute little labels for the kits:

Some amazing pictures are here on Facebook.

The whole idea of the day was teaching kids what they could learn in 6 years in 6 hour-long workshops, as I understood it. There were supposed to be a blogging workshop (Corey Doctorow and the gang at BoingBoing), a programming workshop (run by the indefatigable Walter Bender), a music production workshop (by Queens duo Mysto and Pizzi), a robot building workshop (by Mark Frauenfelder), a hacking workshop (run by the team at Hackasaurus, part of Mozilla), a 3D printing workshop (by the team at i.materialise), a chair-building workshop (by Gever Tulley), and our own soldering “musical” instruments workshop.

Man, I wish I could do that! This may be the blueprint for a future Openlab Workshop. We’ve been toying around with a summer camp… but I digress.

Unfortunately, Corey missed his train and his workshop was canceled, but that worked out in the end because those little kid brains were bursting with gooey knowledge by the end. Think Cadbury’s Creme Eggs, except with more technology crammed inside. There, now you’ve got it.

At the same time, us workshop Capo di tutti capis alternated giving TEDx talks. For myself and the team, this was a first – we’re all big fans of TED, and being on a TED was like walking into one of those epic dreams where you find yourself elected President and your first act is giving a speech before Congress, when you find yourself naked with nothing but a gavel and Newt Gingrich. Well, this was light-years better, because I wasn’t naked and there were few Republican Congressman around.

Some highlights – well, just about all the talks were great. Gever Tulley and his alternative schools that get kids creating, building, and then thinking; Alyson Shafer and her amazingly coherent and thoughtful rush of thoughts on modern parenting; Walter Bender and teaching kids not only programming but debugging (more on this later); then 3D prototyping, gamification, hacking the web… by the end I felt a bit overwhelmed, but in a good way.

Ken Robinson’s call to arms (or, uh, pencils?) for us to change how we educate was one of the best talks I’ve seen. This is a guy who can make reading from a crumpled up note in his pocket one of the funniest and most touching experiences you’ve ever had. It could be the impeccable British accent, or the dry British wit, but there is a lot of substance to go with the belly-laughs.

They put Sir Ken first, which was a bit like throwing out the Beatles on the stage and then asking for the warm-up act to come out and play a few covers. Very intimidating when you’re the warm-up act. Luckily, up next was Alyson, who I hear has to be water-cooled every hour or else she starts to melt things like a Japanese reactor. The woman has energy! And she knows how to use it – she started and ended the day in two 20-minute talks that were both marathon and interesting.

The theme of the talks, and much of the day, was experimentation. Experimenting, as we who practice it understand, means a near-constant state of failure, or as I like to call it, “trying.” Most of the speakers echoed this thought, and how our kids are being raised in a world where failure isn’t an option. Ironically, in an age where videogames celebrate a near-infinite number of “lives” and possibilities, the real world allows fewer and fewer chances. I see this often teaching at British universities, where the kids are afraid to attempt things they don’t know already. They try and play it safe, because they’ve been beat down into thinking that they can only do wrong. Thankfully they have art school (until the government finishes dismembering it) to unlearn that.

Alyson held up the “Solder Sucker 9000” as an example of what we’re missing – this ingenius device is a little spring-loaded pump that sucks up a mistake you’ve made during soldering. It’s an “undo” button for the real world, and it’s interesting that people latch onto it as a metaphor for what’s missing in the high-pressure world of today. To be honest, we gave some workshops with real risks – although very reasonable ones – and the kids did just fine. Kids need exposure to “safe” risks like soldering, woodworking, etc, and less exposure to the “unsafe” ones like drugs, gun crime, cancer, global warming. It’s amazing how we’re desperately grasping at the good risks and still fairly ignorant of the really scary ones. I suppose that’s what we call denial.

Sorry to be preachy, it happens sometimes. Here’s a picture of the nighlife scene in Waterloo, Belgium, to make it up to you:

Moving on, our talk was about the incestuous relationship between technology and creativity. They effect one other deeply, and yet subtly. I spoke about the recent historical context of artists attempting to make work using technology and the high-tech tools of industry; Daniel followed up with a more recent history of the explosion of complexity and the power we now have to starting making things ourselves, and in a more collaborative, open way; Bethany ended with examples of workshops we’ve taught, and what we’ve learned by planning and delivery them to a diverse range of people.

My section of the talk (in written form… different than the spoken version, because I speak better when I have points but not full text to recite) is here:

I want to start our talk by speaking about creativity and technology, and our power over the tools that we use to create our own reality. Creativity is the great enabler of technology – we can do so much with it, but at the same time it fundamentally changes what we do.

Marshall McLuhan said, “We shape our tools and they in turn shape us,” but how many of us actively create the tools, compared to how many of us simply use them?Over the last 100 years, these technological tools have become so complex and specialised. Getting ourselves and our children to take control over them will be a huge undertaking. But it’s worth it, because giving all of us some control over the basic means of expression and of common understanding is essential to the functioning of our democratic societies, and for our own individual sanity.

We use technology to do everything today, from recording images on digital cameras to telling the kids that its time for dinner. It’s our basic medium of conversation, and almost all human expression must pass through it somewhere. We have to rely on websites to translate our intentions, and predictive text message to interpret our feelings between friends, enemies, and loved ones. Interpretation is key – when the artist uses Photoshop or a digital painting program, they submit to the aesthetic of that tool, and it greatly influences their creative process. The technology tells us not only what is possible, but what is right and what is wrong – what is permissible. And that has everything to do with who created the technology and what their system of beliefs was.

Look at iMovie – a pretty innocuous piece of software that many kids (and a fair number of adults) use to make home movies and YouTube videos of their cats jumping into cardboard boxes. iMovie is great for making movies, and making them look good, but it was designed to make certain types of movies, and subtly but powerfully pushes you into a certain mindset and aesthetic making videos than you would have using Sony Vegas, or a physical medium like film, for example.

What we’ve found in our workshops is that people actually are interested in the nuts-and-bolts of technology, from nurses to artists to retired accountants. People want access to what’s under the hood, to change the rules that govern what they’re making and how they’re making it.

To and provide a little historical context, about 100 years ago artists like Marcel Duchamp made machines that were works of art, mechanical creations that moved about and changed shape using simple motors. Not much later, Jean Tinguely made machines that made art, these mechanical, gas-powered drawing devices that could draw pictures automatically. They were so successful that one museum used the profits from the sales of the drawings produced by one machine in the collection to buy another. These hand-made machines hinted at a future where art could be mass produced on an industrial scale.Also, we need to take into account artists’ experience in WWII working in industry, and collaborating with the military building fake, theatrical villages in Britain as decoys for German bombers or developing camouflage patterns for warships. Artists realised that engineers in industry were building things on a scale that they only dreamed of. How were they going to get to use these tools too?

When Tinguely produced “Homage to New York” in 1960, he needed the help of professional engineer Billy Kluver and his friends at Bell Labs in New Jersey. The collaboration inspired Billy, who had an interest in art going back to his undergraduate days, to form an organisation to organise future collaborations. Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) was formed by two engineers, Billy Kluver and Fred Waldhauer, and two artists, Robert Rauchenberg, and Robert Whitman, to bring the artists and engineers together into a collaboration, to give them space to have conversations about the tools and the uses to which they could be put. They paired up willing artists with willing engineers and organised some very ambitious and interesting collaborations including the Pepsi Pavilion at the Expo ’70 in Japan and the seminal series “9 Evenings” in New York in 1968. At 9 Evenings, artists including John Cage’s “Variations VII” debuted, with an arsenal of custom-engineered noise-making and tone-generating equipment that the crowd could manipulate to make sound, along with phones and wireless transmitters. Robert Rauchenberg took a game of tennis between two artists and made it into a contemporary epic, adding wireless transmitters, knock sensors inside tennis rackets, and infrared cameras showing an invisible crowd in the dark, chanting.

E.A.T. was highly influential in certain circles, especially in art, but they soon realised that making singular works of art was a drop in the bucket compared to their goals. The lack of conversation between engineers and industry, who created tools and technology, and artists and the general public, who tried to find a creative use for it, was growing larger and larger. Technical specialists were still making tools mainly for themselves and their peers to use – the conversation between technology and its users was akin to someone sitting in a room muttering to themselves while others looked on in confusion.

E.A.T. proposed some ambitious projects designed to get people communicating with one each other on a national, even global scale, using the tools of mass communication and satellite technology, most sophisticated tools of the time, but with limited success. They formed a core group and inspired interest in some, but the sparks didn’t catch on a larger scale – in the 70’s artists grew wary of industry, and industry grew fed up with artists, and so funding dried up. Organizationally, their movement was limited to being local by the lack of communication technology – no mobile phones, email, websites, Facebook. The spirit and expertise was there, but it never reached a critical mass because infrastructure to make it happen was still years away.

Frankly, watching all of the workshops and talks inspired me to keep doing what I’m doing. I see others thinking similar things, and I’m proud to be part of this movement that has all our best interests at heart. And to be making some very cool things along the way.

Thanks for reading!